- Dr. Andrew Lambert – International Journal of Naval History

- Oliver Walton – Journal for Maritime Research

- Admiral Richard Hill – The Naval Review

- The Nautical Magazine

- Jonathan Seagrave – Soundings

Review by Dr. Andrew Lambert, King’s College London, for the International Journal of Naval History

What was life really like in the navies of Nelson and Victoria? What did officers leave out of their letters home and their published memoirs? James Lowry and John Marx went to sea at either end of the nineteenth century. The first, a young Irish medical student, used the Navy and the Napoleonic wars to make his way in an expensive profession, and saw a good deal of the Mediterranean in the process. The second, the great grandson of a German Jewish doctor, had a long and successful career that demonstrated just how easily immigrants were absorbed into the British elite.

The written remains of these two men repay study because they were never intended for publication. In contrast to the pious platitudes that usually pass for memoirs they record life in the round. Lacking the obvious professional interest in ships and seafaring Lowry spends most of his time recounting the delights of his various runs ashore, and his amorous adventures. Marx found relief from the demands of his career with the denizens of an altogether older trade, and left a clear reminder of the fact in his journal. He records how he and three fellow officers went ashore together. They all caught ‘the clap from the same house at Cadiz.’ (p.68) Like Gladstone Marx used a simple symbol to record morally suspect actions. He also described the infectious consequences with such accuracy that a modern doctor has been able to diagnose! In an age before penicillin Marx took a large number of mercury cures, and indulged in a good deal of sanctimonious remorse for sins he would commit again. Lowry never admits to catching a venereal complaint, but his fascination with the subject outstripped purely professional interest. On joining the Navy he was sent to the accommodation hulk Bedford, where he noted: ‘We had on board 400 prostitutes and of course out of such a number many were diseased.’ (p.31) He went on to observe venereal effects everywhere he went. One suspects he used the old line ‘trust me, I’m a doctor’ as his calling card at many a bordello – while the availability of a ‘cure’ made English surgeons very attractive friends.

Lowry lost his original journal in a shipwreck, so the version we have here was rewritten from memory and sent to his brother. He witnessed the tempestuous years that followed the Battle of the Nile, offering fascinating insights into the Neapolitan Jacobin Revolution, Nelson’s conduct in Naples, the successful British invasion of Egypt in 1801, a brief period as a French Prisoner of war, and the return of Nelson to the Mediterranean in 1803. Nelson scholars will be fascinated to learn that Francesco Caracciolo’s corpse was made to float upright by his fellow rebels. As a surgeon Lowry saw the horrific consequences of battle, terrible injuries, screaming men, and bloodstained decks, men transfixed by massive splinters and limbs crushed. Little wonder he took such delight in female company and polite society ashore, in Naples and Sicily. He came ashore in 1804, fully qualified in his profession, and richly endowed with salty yarns. He reminds us that Nelson’s fleet was crammed full of young men for whom fiddlers and whores were a source of constant delight.

Nor had tastes changed by the time John Marx began his naval life on board HMS Britannia, the floating cadet training hulk at Dartmouth, in 1866. He did well in his studies, but lacked the self-confidence to be a leader. He continued in the same vein for some time, a diffident lieutenant assailed with self doubt, despite the support of neighbour and family friend Admiral Sir Geoffrey Hornby. Hornby’s support kept his career moving along, until he hit his stride as a commander with his own ship. From this point on Marx showed himself to be a man of superior talent, resourceful, and confident. His actions on the African station were typical of the best of his generation. The combination of righteous zeal and effortless superiority that marked out the officers of Victoria’s Navy from all other men ensured he had no hesitation in acting against slavers, smugglers and other riff-raff. As editor, Dr. Mary Jones observes the transition from the largely independent Imperial cruisers of the Victorian navy to the tightly controlled Edwardian battle fleets did him few favours. Because he had little fleet experience he was retired as a captain in 1909 – a victim of John Fisher’s fleet concentration policy. However, the Royal Navy was not done with him.

When war broke out in 1914 Marx went to London and pestered the Admiralty until they gave him a job, as a captain in the Royal Naval Reserve – rather than his actual rank of Admiral of the Retired List. Commanding in armed yachts and decoy or ‘Q’ ships he played his part in the anti-submarine war – delighting in the independence of his command, the challenge of finding the enemy and the camaraderie of the wartime Navy. He didn’t sink a U-boat, but for years he was convinced he had. Only when the captain of the U-boat wrote to him did he accept that the damage inflicted had not been fatal!

Like many a naval man home from the sea Marx loved the countryside of his South Hampshire childhood. After the war, having retired for a second time, he took up fox hunting, unpaid civic duties, charitable concerns, farming and gardening with the same zeal and energy he had employed at sea. His last act was to build an air raid shelter, ready for the Second World War. He did not live to use it, dying in mid August 1939.

Editor Mary Jones has used Marx’s surviving diaries and letters to create a fresh and vivid picture of a Victorian sailor·s life. The reality of a service career combined constant anxiety about promotion and prospects ambitions with frequent runs ashore. Young officers ended up in the most insalubrious areas of many seaport towns, and like the men they led, frequently got more than they paid for. Venereal disease was an occupational hazard – and a good surgeon was a real friend. For all their professional ambitions they were human, and fallible. Marx was a good officer, he knew his business, but he lacked the killer instinct to make the highest grades.

The accidental survival of Lowry and Marx’s accounts has provided a powerful corrective to the usual naval memoirs, texts carefully edited to avoid offending maiden aunts, spouses or offspring. Naval officers did not live Spartan, monkish lives of absolute dedication, abjuring the sins of the flesh. Nelson’s infidelity was not the exception, it was the rule, Lowry was completely uninterested in the subject. When those old memoirs were written the Admirals filled them with endless tales of runs ashore to slaughter the local avian population. Perhaps they were resorting to an old trick – if Marx’s account is to be trusted the ‘birds’ they pursued were not of the feathered variety!

These two books provide a novel perspective on the great events of war and empire, appealing to anyone who has wondered just what naval officers did when they were not on duty.

Visit the International Journal of Naval History website

Review by Oliver Walton for the Journal for Maritime Research Journal Issue: July 2007

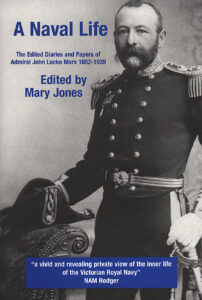

A Naval Life book cover The Royal Navy of the second half of the nineteenth century saw profound institutional and social changes. However we have few good sources for how individuals experienced life in this changing service. Mary Jones has unearthed an extensive private archive belonging to a ·minor· naval officer, John Marx, who had a full and colourful career, though he never reached the heights of command as an admiral.

Jones’s tale comprises sixteen chronological chapters which are organised around the significant stages in Marx·s naval career. They take us from his youth and entry in 1866 to training on HMS Britannia up to his death in 1939. Marx circumnavigated the earth in Phipps Hornby’s Flying Squadron and served on stations across the globe, from North America and the West Indies, Australia, East Africa and the Pacific as well as those closer to home like the Mediterranean and the Channel before retiring as a Rear Admiral in 1909. He also embarrassed the Admiralty into employing him during the First World War, serving on anti-submarine and convoy escort duty.

What emerges is a story of an unexceptional career of a competent officer who happened to enter the navy at the right time; promotion became unblocked steadily as Marx’s career progressed, while from the 1890s naval expansion opened up further opportunities for promotion. Marx did indeed have a full career, though his lack of experience with fleet operations and lack of connections with Jackie Fisher probably held him back from major command.

Yet there are other stories which underlay this one. Marx recorded many frustrations with his professional life. The regime of shipboard life often seems to have been claustrophobic. Marx often escaped, whether by going off on a canoe trip, going mountain climbing or visiting a brothel. It is far from clear that he found the naval life fulfilling. Certainly he seems to have relished some of the practical challenges offered by ·action·, whether supporting naval brigades ashore, fighting fires in Turkey or ensuring the safety of his ship in heavy weather. But the discipline, the institution and its politics seem to have been at times oppressive and perhaps bemusing. While he enjoyed society, especially that of women, he seems not to have been a natural at ·networking·: the patrons who supported him were senior officers he had impressed on the job. He was perhaps too independent-minded to play the more ·political· games which might have helped him in the latter stage of his career.

This independent-mindedness, born partly of the culture underlying Marx’s training and partly from his extensive experience patrolling the outer reaches of the empire, Jones sees as quintessentially ‘Old Navy’. This she contrasts with the New Navy, characterised by greater emphasis on spit-and-polish, precise manoeuvres of large squadrons and, especially after the loss of HMS Victoria in 1893, less room for individual initiative in the unswerving obedience to orders. There is of course a great deal of truth in this characterisation. However, the dichotomy of ‘Old’ and ‘New’ navies obscures the novelty of the navy which Marx himself entered in 1866. His career was characterised by the institutions of a technocratic and profoundly modern professional navy, with its training ships, colleges and examinations, not only to regulate entry to the career but also to control progression throughout the career. Of these only the Lieutenant’s examination was older than the mid-nineteenth century. Moreover, the navy in which he served also had a new social order, created by the introduction of continuous service for ratings in the 1850s and the passage of the naval discipline acts in the 1860s.

Jones writes with fluency, though a few sentences are perhaps overly colloquial. The storytelling is compelling. In this Jones is most ably assisted by Marx himself, and the scope of the papers he left behind. His diaries are most personal pieces of writing, even recording his sexual and romantic exploits. Not often given to deep introspection, he still allowed himself to vent his frustrations with work, with others and with himself onto the page. There are also letters to and from other officers and correspondence with his family. The result is a record which permits Jones to interweave the professional and the personal.

Jones is effective in using quotations to allow Marx and his correspondents to tell much of the tale themselves. Furthermore, some of these quotations can be quite lengthy; far from disrupting the narrative flow these serve to illuminate the portrait of Marx. There are sometimes large gaps in the chronological coverage of Marx’s papers. Jones ·plugs· several of these by drawing judiciously upon other sources. The largest gap is down to Marx’s papers: as is so often the case among the personal papers of naval personnel, there is least to illuminate life on the stations nearest home. For our understanding of Marx this is particularly frustrating, since this leaves largely blank the first few years of the twentieth century when he was Captain and had several commissions in the Channel and Mediterranean Squadrons. These commissions were likely have been the making or breaking of his career and the greatest test of how Marx was ability to command in the larger ships and fleets of the Edwardian navy.

There are a couple of minor inaccuracies: Haslar Hospital was in Gosport, not Portsmouth (pp.79-80); ‘seedies’ were Muslims recruited in the Indian Ocean as additional unskilled manpower (p.199). It might also have been good to include some more analysis of Marx’s capabilities and style as a shipboard commander.

These criticisms should not detract overly from what is a lively and insightful biography based upon a good deal of detailed research. Marx’s papers give often very candid expression of Marx’s experiences and character and Jones presents his story well. This is a valuable work which portrays some of the realities of life as a naval officer which lie behind old admirals· anecdotes about snipe shooting.

Visit the Journal for Maritime Research website

Review by Admiral Richard Hill for The Naval Review – February 2007

The subject of this 280-page work was not an officer of vast distinction, nor a notable hero (though his First World War DSO was well-earned), certainly not a major innovator nor an administrator of the first rank. Yet this edition of his papers has much to contribute to the history of the period.

Firstly, the span of Marx’s service, from 1866-1918, covered a period of rapid transition in both technology and strategy. On technology, there is now a robust consensus that the Royal Navy adopted or adapted new techniques, in general, more effectively than did other navies, partly through the readiness of those in charge to accept change, but also because of Britain’s superior industrial base and maritime infrastructure. As to strategy, there is still argument about how much change was imposed by external developments, and how much was internally generated by Britain’s vision of her own role; but change there certainly was, the emphasis on imperial expansion shifting to a more centrist defence policy as the century turned.

The commentary in this book differentiates sharply between ‘Old Navy’ and ‘New Navy’ in these two areas. Most of Marx’s formative service, up to and including his time as a junior captain, was in more or less remote foreign stations, in gunboats and cruisers, with many minor naval brigade operations. It is frequently referred to as ‘Old Navy’ and suggested that this was Marx’s natural habitat, as a seaman of increasing experience and resourcefulness. His time in the ‘New Navy’, particularly the Channel Fleet in the early l900s, is implied to be neither so happy nor so successful. His command of a ‘Q’ ship in the First World War (on reversion to the rank of captain) was, it is suggested, ‘Old Navy’ at least in concept and therefore more appropriate for him.

Readers may not entirely accept the sharp distinction between Old and New. The strategic transition was often subtle and shifting; after all, 1878 saw a massive exercise in deterrence by the Mediterranean Fleet (and Marx was there in fact), while there was still plenty of imperial derring-do up to and after 1900. Similarly, there was a lot of overlap in technology; for example, cruisers on remote stations had to rely on sail, because coaling stations were few, long after the main fleets were almost entirely steam powered. But with this caveat, Marx’s views and attitudes are instructive.

The other contribution this memoir makes is social. Marx had what the Foreign Service euphemistically calls An Eye for a Pretty Girl. The medical scrapes into which this led him are reported in some detail, frequently accompanied by must-do-better homilies to himself – he had a strict upbringing. They did however recur and it is clear that it was not only the nineties that were Naughty, but the seventies and eighties as well. The acceptance of risk, not only by Marx but many of his brother officers, is revealing.

The chief value of this book may well lie in the very ordinariness of its principal character. Marx was the sort of officer Palmerston spoke of in his well-known eulogy (…’I send for a captain of the Royal Navy’…) – practical, sound and often resourceful. The country owed him, and his kind, a lot.

Visit The Naval Review website

Review from The Nautical Magazine

THIS is by no means a conventional biography. Indeed, there are times when the protagonist’s record of events in his diaries and journals, and the author’s examination of many personal and public records, produce a startling view of the Victorian Royal Navy.

Much effort has been made to present the man, warts and all. Following his birth in 1852, comes an account of family and childhood background in rural Hampshire, complete with a fox-hunting father and a devout mother. Influential friends of the family help get him nominated as an RN cadet, and then it’s life aboard the training ship Britannia, with letters home complaining of discipline, punishments and bullying. Then it’s joining a frigate as a Junior Middy and even more things to bleat about. Soon it’s 1870, he’s 18 years of age and a senior midshipman. At this point his first journal starts. And it is his record of doings on and off the ship, time on the sick list after catching disease ashore viewed alongside matters of seamanship, naval gunnery, navigation, etc., that sets the tone of what follows; a record of the progress of a personality manoeuvring within warships, acquiring then plying the skills that go to making a naval officer, whilst rebounding off superiors and subordinates and, if time spent on the sick list is anything to go by, confirming the view that for a sailor there are more risks ashore than at sea.

A record of what ships he served on and in what capacity along with the various training courses he attended, is contained in a two-page chronology at the start of the book; everything from serving as a cadet aboard Britannia, in 1866, to his final appointment as Admiral, Flag Officer Convoy Escort that ended in 1918. How he performed as a midshipman, junior officer, first lieutenant, his first command of a gun boat on the Australian Station is recounted, including his Antipodean marriage. Promoted Commander then very quickly, Captain, it’s off around East and West Africa protecting British interests from ‘cheeky’ natives and developing his diplomatic skills alongside gun-boat diplomacy at a time very much ‘British Empire’.

A great deal examined here, everything from ship handling, organising shore assault parties, handling his officers and men, outmanoeuvring his superiors, to being invalided back home on sick list for a year.

The author stresses the adjustment needed by somewhat like Marx, whose professional development had taken place entering a Navy of spar, sail and smooth bore cannon, and where the autonomy of the likes of gun-boat captains abroad in distant seas was legend, to the start of the 20th century where steel, steam, triple turrets and torpedoes were the order of the day. On that count, an appointment to a command in the Home Fleet within sight of Whitehall took some adapting to. In fact, his Admiralty superiors, in some cases affronted by his singular temperament, at the same time they promoted him Rear Admiral in 1906, saw to it he got no sea-going appointment between then and his retirement in 1909.

WW 1 and 1914 sees Admiral Marx RN Rtd parked on Whitehall steps, happy to accept an appointment, Capt RNR, along with 6 armed trawlers for anti-submarine work. After a couple of years scuffling with the odd German submarine, it’s captain of a Q-boat and more anti-submarine exploits. He sees the war out in convoy escort ships. Finally, on the retired list in 1919, the account details interests ashore ranging from fox-hunting to seafarers· charities. He dies in 1939.

There is much to intrigue here. Very much a description of a personal encounter with the times and the attitudes that prevailed in both naval and civilian society of the day.

Review by Jonathan Seagrave for Soundings, the magazine of the South West Maritime History Society (October 2007)

Mary Jones life of Admiral John Marx is unusual, for an era of admiral biographies, in being sourced from very private diaries most definitely not intended for publication. One imagines his shade may blush at some of the youthful intimacies revealed, though he was no different to many of his peers.

He came from a well off, but not naval, Hampshire family and joined Britannia as a boy. His youthful letters show both the roughness and attraction of the training system, and adolescent self-doubt.

Once at sea he finds naval life challenging and not always rewarding, but eventually finds his feet and builds his confidence. He is both judgmental and fair-minded towards his fellow officers. He also goes on technical training when it was unfashionable, and this may have served him well later in the modernised Fisher navy, although he was never part of the Fisher circle.

Overall his career follows a trajectory of accelerating action. His first years are in the languid waters of the Mediterranean, although he is present at tense moments in the Dardanelles, and learns lessons in diplomacy he will use later on. He twice rescues men overboard, he says for the medal and promotional status. Both rescues stretch him physically to the limit, and the courage required is beyond doubt, especially for one never over strong, and plagued by illness from time to time. Even in those peaceful times, sudden death by accident or illness was never far away.

He is posted to the African stations, both East and West, where there is considerable action. The account whilst in HMS Fawn, of action in narrow creeks to restore peace in Sierra Leone, brings to mind much more recent interventions there. Plus ca change. He shows little of the snobbery of the era, and takes a real interest in the local customs and people. He shows his temperament as an Old Navy man, far away from superiors, independent of mind, looking at the purpose of orders, and showing great initiative and energy in dealing with the situations he finds.

His sails his first command, the gunboat HMS Swinger, to Australia, where he deals briskly with slavers in the Pacific islands, and meets his future wife Lily, a formidable lady. This seems to have been a practical marriage of independent spirits, rather than a great romance, and there are hints of tolerance of his keen eye for pretty women.

On his return to England he is promoted and follows a career largely in command of cruisers. On the Caribbean station, commanding HMS Proserpine he has to be extremely diplomatic, and works with a US navy vessel to protect British interests in a revolutionary situation.

He returns to the Atlantic fleet, but the world of the New Navy, and centralised command of large fleets is not really his style. He is assessed as wanting practice handling ship and fleet. Nonetheless, he remains committed to his career, but retires in 1909 to his home in Hampshire and his beloved hunting.

The next stage of his career is quite extraordinary. On the outbreak of war in 1914, at 62, he becomes a cause celebre, camping out on the Admiralty steps, till given a seagoing post as a RNR captain. I won’t spoil the story for you; suffice it to say that he more than shows the virtues of his era, courage, endurance and commitment in doing duty, in some exceedingly tough and stressful postings -a very long way indeed from the balmy life of the socialising young officer in the Med.

The book is an easy read, and the author has researched and cited widely, and placed the life firmly in the context of the times. There are inevitably some gaps where the papers or other records are missing, and the fascinating private diaries largely run out in later years. No doubt with age, rank, and confidence, he became both more discreet and less prone to reflection. There will always be a slot for an update in Soundings if any more material turns up! Illustrations include his first and last regular commands, HMS Swinger and HMS Dominion, and the usual family photos and portraits.

I came to feel I liked the man very much; and I much enjoyed, and recommend, the book.