In Kipper part two, Carl Clayton, completes the remarkable history of Rear Admiral Robinson, VC. We see Kipper’s exploits in the naval war against the Bolsheviks at the end of WW1, his involvement with the U-boats as a convoy Commodore in WW 11 and his valuable diplomatic work with an international flotilla at Dundee. In putting all this into context, Carl Clayton gives us a splendid review of the contemporary historical background. Highly recommended reading.

13/6/22 – Chapter 5 has been revised in the light of new information discovered by Steve Mills about Eric Robinson’s involvement in the secret Distantly Controlled Boats section of the Royal Navy between 1917 and 1918. The author is grateful to Mr Mills for permission to use this research to add yet another chapter to Kipper’s career.

To read Part 1 click here

Contents

5. Kipper and the Red Menace

6. Kipper and the U-boats

7. Kipper in Dundee

8. Kipper stands down

Bibliography

Chapter 5. Kipper and the Red Menace

In 1916 after recovering from his Gallipoli wounds, Kipper (now Commander Robinson VC) was given his own command, the monitor HMS M21 operating off the coast of Palestine. Monitors were small warships fitted with a single large calibre gun which provided artillery support for operations on land and Kipper was to play a small part in the continuing war against the Ottoman Empire.

In January 1915 Ottoman forces had attacked Egypt and the strategically important Suez Canal but were stopped by the British forces. The position remained static as the attention of both sides shifted to Gallipoli. Then in August 1916 Ottoman, German and Austrian force launched another attack, but this was repulsed and the British and Anzac army went on the offensive. The Ottoman forces were pushed back across the Sinai Peninsula into Palestine. On the 26th March 1917 the British commander, General Archibald Murray, launched an attack on Gaza with the intention of breaking through the Ottoman lines and advancing on Jerusalem. British and Anzac troops were on the point of capturing the town when they were ordered to withdraw. A few weeks later another attempt was made to capture Gaza, but by now the Turks had strengthened their position.

HMS M21 took part in the initial bombardment for this 2nd Battle of Gaza, supporting the land batteries. Its 9½ inch shells rained down on the enemy lines but two days of shelling, which included the use of gas shells, had a limited effect on the Turkish defences and served to warn the enemy that an attack was imminent. The attack failed resulting in the dismissal of General Murray. The Turkish lines were not breached until October 1917 at the Battle of Beersheba and Gaza finally fell in November. Jerusalem was captured the following month.

Despite the failure of the 2nd Battle of Gaza no blame was attached to Kipper and he was awarded the Order of the Nile for his services. His first solo command had been a success, but a naval monitor was hardly suited to someone of Kipper’s skills and temperament. His next posting was to be very different.

In September 1917 the Royal Navy set up a secret experimental section, attached to the Signals School Portsmouth, to develop the remote control of unmanned surface craft by radio from seaplanes. For the purpose of secrecy, the vessels controlled in this manner were known as D.C.B.s standing for Distantly Controlled Boats. Kipper was appointed commander of the DCB section.

The Navy had recognised the potential of using aerial torpedoes to attack enemy ships, but aircraft of this period could not carry a large enough torpedo to sink a capital warship. The aim of the DCB section was to develop a surface vessel carrying a large explosive charge that could be controlled remotely by radio from an aircraft and directed onto a target – effectively a large, surface torpedo. This was very advanced technology for its time and built upon technology developed by the Royal Flying Corps for unmanned aircraft to be used as ‘Aerial Targets’. Clearly a high speed and manoeuvrable craft would be needed for the role of DCB and a good candidate was the Coastal Motor Boat or CMB.

CMBs were small powerful motor boats with a 250 hp aviation engine capable of speeds up to 40 knots. Armed with torpedoes or depth charges they were the forerunner of the Motor Torpedo Boats of the Second World War. Developed by the naval builders Thornycroft in 1916 they were to prove themselves very effective as their high speed and small size made them difficult targets. Later a slightly larger version was produced with two 375 hp engines and a top speed of 45 knots. A feature of these boats was that the torpedo was launched tail first from a trough over the stern of the boat. The crew of two or three men aimed their boat at the target and then released the torpedo so it was heading towards the target in the wake of the CMB. The CMB then had to swerve out of the path of the torpedo to allow it to run towards the target.

For its role as a DCB the torpedo was unshipped, and a large explosive charge was fitted in the bow. A receiver unit connected to gyroscopic steering gear was fitted in the CMB and this could be controlled by a sender unit fitted to the aircraft. Many technical issues had to be overcome but by May 1918 trials showed that the boats could be steered on various courses and directed through a narrow gap between two moored launches. In July Admiral David Beatty, the Commander-in-Chief, Grand Fleet was asking for details of the trials and in September Admiral Sir Ragnar Musgrave Colvin reported that:

“Wireless controlling gear for steering a vessel from an aircraft, ship or shore station is an accomplished fact, and can probably be fitted to any type of vessel.”

Serious consideration was being given to deploying the DCBs in an operation, perhaps in the Mediterranean, when the Armistice was declared on the 11th November 1918.

Kipper had used his knowledge of wireless telegraphy and electrical engineering to coordinate the work of the scientists, engineers and naval personnel and bring the secret DCB project to a successful conclusion. At the same time he had learned how to operate the fast and agile CMBs, and this meant that for Kipper, the war was not over. In January 1919 Kipper was put in command of a unit of 12 CMBs dispatched to the Caspian Sea to fight a new enemy – the Russian Bolsheviks. To understand why the Royal Navy were operating in this new theatre of war we must go back to 1917.

The war had imposed great strains upon Imperial Russia and, following strikes, riots and mutinies, the Tsar abdicated and was replaced by a Provisional Government under Prime Minister Alexander Kerenski. The democratic reformers of this Provisional Government looked to the western democracies for support and were committed to continuing the war against Germany, but they did not have the support of the whole country. In November 1917 (October by the Julian calendar then in use in Russia) the Bolsheviks seized power in Petrograd and other major town. Civil War broke out between the Reds and their opponents the Whites. The White forces however consisted of a range of groups with little in common except their opposition to the Bolsheviks. Some were tsarists fighting for the restoration of Tsar Nicholas II while others were democratic socialist who wanted a republic. Many nations seized the opportunity to declare their independence from the Russian Empire and were determined that the neither the pro- nor anti- Bolshevik forces would deprive them of that freedom. In addition there were many groups loosely known as Greens or anarchists which took the opportunity to seize land and property and fight anyone who tried to resist them.

Early in 1918 three nations in the south of the Russian Empire, Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan, made a bid for independence. At the same time the Bolsheviks seized power in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan and the centre of a rich oil producing area. With the collapse of the Russian armies the Turks seized the opportunity to advance from the west towards Baku. They were supported by the Muslim Azerbaijanis but opposed by the Christian Armenians, Georgians and Russians. The British wanted to send troops from Persia, at the south end of the Caspian Sea, to Baku to prevent the oil-fields from falling into the hands of the Turks but the Bolsheviks in Baku would not agree to this. When the Bolsheviks were overthrown by a coup in July 1918 a British force under General Dunsterville was finally dispatched only to be driven out in September by the advancing Turks.

By November 1918 the situation changed again. Turkey surrendered on the 30th October and withdrew from Baku. The British sent another force to support the White Russians against the Bolsheviks. Troops, tanks and a squadron of aircraft were sent to Baku, and a naval squadron was formed to control the Caspian Sea. As the Sea is landlocked and the Royal Navy could not sail there, Britain requisitioned several Caspian merchant ships and fitted them with guns. Commodore David Norris led this flotilla which had British officers and a few British ratings. The rest of the crew were Russians. Some of the ships, such as HMS Kruger, Slava, Zoro-Aster and A Yusanoff kept their Russian names, others such as the Windsor Castle, Dublin Castle and Edinburgh Castle were given distinctly British names. In the words of a researcher at the National Maritime Museum it was “one of the least likely gatherings of ships for the application of sea power there has ever been”.

To reinforce this odd collection of ships the Navy decided to send the twelve CMBs from England. They were loaded onto a transport ship and taken through the Mediterranean. They passed through the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus into the Black Sea to be disembarked at the port of Batum. Here the CMBs were loaded onto flatbed railway trucks and taken to Baku by rail.

Baku was a once elegant town which had fallen into decay. When oil had been discovered at the end of the nineteenth century it had been one of the wealthiest cities on earth. Famous European luxury stores opened branches on Baku’s elegant tree-lined avenues and the newly rich oil barons built themselves magnificent palaces and villas. Even before the war the decline had begun with a series of strikes, riots and ethnic strife. The population of the city was made up of Muslim Azerbaijanis and Christian Armenians and Russian. In April 1918 many thousands of Muslims had been massacred following fighting between the Azerbaijanis and the Bolsheviks. The capture of Baku by the Turks in September 1918 had allowed the Muslims to gain some revenge for this. Now there was an uneasy truce as the different groups tried to unite against the Bolsheviks.

When Kipper arrived in Baku he set up his headquarters in a hospital. The CMBs were unloaded from the railway trucks by derrick and lowered into the water. They were now ready for action.

The nearest Bolshevik naval forces were in the port of Astrakhan at the northern end of the Caspian Sea. This port was ice-bound in the winter so there was no danger from that quarter until the spring. However, there was another threat closer to hand. During the war a Russian naval unit known as the Centro-Caspian Flotilla had been based at Baku. This force was still in existence and in theory was meant to co-operate with the British, but the long period of inactivity had led to a collapse of efficiency and discipline. The British feared that the Russian sailors had pro-Bolshevik sympathies and would go over to the other side at the first opportunity, and it was decided to disband this flotilla by force if necessary. On the morning of March 1st 1919 the flotilla commander Colonel Voskrensky was summoned to the British HQ and told that if the ships did not surrender they would be sunk. Voskrensky agreed on the condition that he was given a safe passage out of Baku, but there was no guarantee that the crews on board the ships would follow his orders. Those ships that were tied up in the harbour were immediately boarded by British troops, but two gunboats and some other ships were now anchored outside the harbour. Commodore Norris on board his flagship HMS Kruger dispatched an order to Kipper that he was to proceed to sea with his CMBs and order the ships to surrender. If they refused, he was to torpedo them.

Kipper led four CMBs out to deal with them. The orders to surrender were read out to each ship in turn and the CMBs then turned away. The minutes ticked away to the deadline but there was no sign of movement from the ships. The engine of Kipper’s boat roared into life and it sped across the water towards the leading ship. At the last moment the torpedo was launched from the stern of the boat and the CMB swerved aside to allow it to run towards the target. Whether by accident or design the torpedo ran deep and passed underneath the Russian ship but the sailors on board had got the message and all four ships surrendered and returned to port.

It was known that Astrakhan would be free of ice by early April and that the Bolsheviks were preparing armed ships including destroyers. Commodore Norris, the commander of the British squadron, decided to move further north to Chechen Island to keep a closer watch on the Bolsheviks. Four CMBs were left at Baku and four were sent to the port of Petrovsk, midway between Baku and Chechen. Norris realised that his squadron needed a long range scouting and striking force so he converted some of his merchant ships into carriers. HMS Orlionoch and A. Yusanoff were equipped as seaplane carriers with two biplanes fitted with floats. These could be hoisted over the side of the ship onto the water from where they would take off to fly their missions. On return they would land on the water next to the ship and be hoisted aboard for refuelling. HMS Sergie and Edinburgh Castle operated in a similar way but carried two CMBs each. In this way Norris planned to use his CMBs and aircraft against the Bolshevik ships and Kipper was put in charge of this carrier group.

Throughout April and early May 1919 there were a number of minor clashes with Bolshevik ships. On May 15th the British squadron carrying out reconnaissance off the port of Fort Alexandrovsk in the north-east of the Caspian, spotted a convoy of three armed ships towing two barges, escorted by a destroyer. The warships abandoned the barges and fled. Norris had to let them escape and turned his attention to the two barges, one of which had quickly run up a white flag. When a boarding-party reached this barge they discovered that the white flag was in fact a pair of under-garments belonging to a lady of 60 who was one of the crew on the barge. By questioning the crew the British discovered that a large Bolshevik naval squadron was now based in Fort Alexandrovsk and consisted of eight destroyers, six to eight armed merchant ships, two or three submarines, motor boats and some support ships. Norris decided that he had to investigate this further.

On the 21st May the British squadron approached Fort Alexandrovsk. His force consisted of the armed ships Kruger, Windsor Castle, E. Noble, Ventuir, Asia and three carriers, Sergie, Edinburgh Castle and A Yusanoff. The three carriers were only lightly armed so they were detached a few miles to the south out of harms way. The other five ships approached the harbour and sighted a number of Bolshevik ships. Some torpedo craft outside the harbour fled to the open sea and others opened fire and then retreated up the harbour. At this point Norris decided to attack the harbour. Signalling to his squadron the Biblical quotation “We are going up unto Ramoth Gilead” he led his force in line ahead into a harbour containing an unknown and partially hidden enemy squadron and possible shore batteries. The action could have been a disaster. As it was the E Noble was hit in the engine room and only just managed to keep going, while the Kruger was also hit and almost had her steering gear disabled. The Bolshevik ships retreated to the far end of the harbour behind a line of barges and because of the short range of the British guns and the narrowness of the harbour, combined with heavy fire from the shore battery, it proved difficult to engage the enemy closely. After about 90 minutes of action the British Squadron turned around and sailed out of the harbour.

Nine enemy ships were sunk or blown-up and in the words of Commodore Norris they were given a “pretty good thumping”. The squadron stopped just outside the harbour and tried to send a radio message to Kipper with the idea of launching a CMB attack early the next morning. Unfortunately the radio was not working properly and the carriers failed to get the message. The failure to bring the CMBs into action meant that the opportunity to deliver a coup de grace had been missed and both Norris and Kipper were left feeling frustrated.

The next day a seaplane from the carriers carried out five attacks on the harbour and claimed several hits. The pilot reported that the enemy were deserting Alexandrovsk and Norris decided to reconnoitre again with his two remaining undamaged ships Kruger and Ventuir, with the carriers, again detached to the south. As dawn broke two large enemy destroyers were sighted. These ships were faster and carried larger guns than the two British ships and things looked bleak for Norris’s tiny fleet. A radio message was sent to Kipper ordering him to get his carriers to safety and Norris ran south-east in an attempt to hide against the shore. The destroyers soon drew ahead of the British ships and closed in for the kill. Shells began to straddle the ships and as Norris confessed later it seemed that the Bolsheviks had “got us cold and our number was up”.

Kipper had received the radio message telling him to withdraw but he decided to turn a Nelsonic blind eye to this order. Instead, he steamed directly towards the battle while attempting to deploy his CBMs. The conditions made this impossible but the Russian commander spotted the smoke of Kipper’s division on the horizon and concluded that he was being drawn into a trap, so he turned round and departed. Kipper’s bold disregard for orders had saved the day.

Five days later aerial reconnaissance confirmed that the Bolshevik forces had withdrawn from Fort Alexandrovsk. This time Norris decided to send in the CMBs. Kipper led the attack into the harbour and sank an armed barge. Immediately a white flag was raised above the harbour and a deputation came from the shore to surrender the town to the British. The wrecks of several ships sunk in the previous raid were discovered but it was realised that a large part of the Bolshevik fleet had escaped to Astrakhan.

The Bolsheviks retreated to the safety of the Volga River delta where they were protected by heavily armed barges. They refused to come out and give battle on the open sea while the British force was too weak to attack them. For a time it looked as though Astrakhan might fall to the White Russian forces of General Denekin attacking from the east but the Reds held their defensive positions. The Whites called on the British flotilla to support their attack on the town, but the British rejected these calls, pointing out that the sea was too shallow close to the land for their ships. This was undoubtedly true but it must have left the Whites feeling that the British intervention force was a token presence.

Back in London Winston Churchill reported the British victory at Fort Alexandrovsk to Parliament in August 1919, but pressure was growing to withdraw the British forces from Russia. It was becoming clear that the Bolsheviks were not going to be defeated and Britain would have to come to terms with Lenin. It was decided to withdraw the British personnel from the Caspian before the winter and hand over the British flotilla to the anti-Bolshevik forces. Even this caused problems as neither the White Russian army nor the Azerbaijanis wanted the ships to come under the control of the other side. Eventually the hand-over was organised and at the beginning of September 1919 the British forces left Baku by train for Batum.

Resistance to the Bolsheviks was short lived. The Transcaucasus governments of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia were unwilling to throw in their lot with the White Russians under General Denekin, who opposed their independence. In March 1920 the White Russian forces were defeated and the Red Army advanced to the borders of Azerbaijan. Another uprising in Baku led to to a Bolshevik Revolutionary Committee seizing power. An Azerbaijan Socialist Soviet Republic was declared, and the country would not regain its independence until 1991.

Meanwhile, Kipper’s contribution to the fight against the Bolsheviks was recognised. The White Russians awarded him the Order of St Anne and he was also made an officer of the recently created Order of the British Empire. On the 31st December 1920 his distinguished war service culminated in promotion to the rank of captain.

Chapter 6. Kipper and the U-boats

In the autumn of 1919 Kipper finally returned from the Great War to his wife and family. Kipper’s son Patrick was now five. A second son, Edward (but known as Tim) had been born in 1917 and a daughter Sheila in 1918. He settled into the routine of a naval career. He commanded the Second Destroyer Flotilla in HMS Shakespeare and Spencer and the Sixth Destroyer Flotilla up to 1925. From 1926 to 1928 he was on the torpedo school ship Defiance. In 1928 he was appointed Captain of the County-class heavy cruiser HMS Berwick on the China Station under Vice-Admiral Tyrwhitt. The China Station was a naval formation with responsibility for the coast of China and its navigable rivers, the western part of the Pacific Ocean and the waters around the Dutch East Indies. It was based at Singapore, Hong Kong and Wei Hai Wei and its role was to protect British shipping and commercial interests in China. In this period the China Squadron worked closely with Japan which had been a British ally during the First World War and in 1929 Kipper was awarded the Japanese Order of the Sacred Treasure (3rd class), equivalent to the British OBE, as were many British officers. The rise of Japanese militarism and anti-western sentiment in the 1930s put an end to this cordial relationship.

In 1930 Kipper returned to England and commanded the artificer’s training establishment HMS Fisgard until it moved ashore in 1932. He was then appointed Captain of the Dockyard, Deputy Superintendent and King’s Harbour Master at Devonport, Berehaven and Pembroke. At the age of fifty his naval career was coming to an end. In June 1932 he received a letter from the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty informing him that they were unable to offer him a post as a Flag Officer on the Active Lists. Kipper was placed on the retired list with promotion to the rank of Rear-Admiral. He must have thought that his fighting days were over and that he could look forward to a peaceful retirement with his family. But for Kipper and the world at large, dark clouds were gathering.

His mother, Louisa died in 1934 at the age of 88. Then in March 1938 at the age of only 46 his wife Edith died.

In August 1939 Kipper received a letter postmarked Berlin and addressed to Rear-Admiral Sir Eric Robinson. It contained a pamphlet “The Reply to English Propaganda” by Reich Minister Dr Goebbels. This pamphlet, no doubt circulated widely to naval officers, was in reply to an anti-Nazi letter from a British naval officer. Goebbels’ pamphlet began by attacking incidents from British Imperial history, such as the Amritsar massacre. It concluded:

“Your English propaganda tricks are absurd. There was a time when we National Socialists possessed no power, and yet we were able to overcome our political opponents at home. That trained us in the work of propaganda. From 1914 to 1918 you were dealing with a nation that was practically unprepared. The position today is different. We are now a politically-minded nation and we know what is at stake. Tomfoolery such as that contained in your letter can no longer bamboozle us. You can tell those little tales to the marines, you honest old British Jack-tar.”

It is not clear what effect Dr Goebbels expected his letter to have on the “honest old British Jack-tar” but Kipper had already made his reply. The previous year he had volunteered to serve as a Commodore of Convoy should war break out.

Convoys had been introduced during the First World War in response to the loss of merchant ships to U-boats. There had been opposition to the idea that ships should sail in convoys rather than individually because it was felt that a submarine would be more likely to spot a group of ships and would then have more targets. In practice a convoy was no easier to find in the vastness of the Atlantic than an individual ship and there was statistically less chance of a U-boat coming across a target. In addition the convoys were protected by warships. Britain decided to introduce the convoy system for merchant ships from the start of the war and the first Atlantic convoy sailed on the 7th September 1939. However the Royal Navy was ill-prepared for the challenge ahead. There had been no peacetime practice in managing convoys and inter-war defence cuts had left the Navy short of ships to act as escorts. As a result an emergency programme of building small escort vessels called corvettes was begun. This filled the gap but the corvettes were small, lightly armed and slower than the U-boats they would have to face.

An essential element of the convoy system was the Ocean Convoy Commodores. These Commodores were naval officers who served on board one of the merchant ships in the convoy. The Senior Officer of the Escort Group (SOE) was in overall command of the convoy and the Convoy Commodore below him was in command of the ships of the convoy. He passed orders on to the Masters of the individual merchant ships who were civilians and an independently minded group of individuals at the best of times. The best account of the Convoy Commodores is given by Alan Burn in his book The fighting commodores: convoy commanders in the Second World War.

Because of manpower shortages the Royal Navy could not spare serving officers for this role. Instead they turned to retired naval officers with considerable experience. In 1943 out of 181 Ocean Commodores 11 were retired Admirals, 33 Vice-Admirals, 53 Rear-Admirals, 14 Royal Navy Captains and 57 Royal Naval Reserve Captains. Officers were typically recalled to duty at a lower acting rank than that held upon retirement. This was so that they would not outrank or even be equal in rank to active duty officers who might be commanding flotillas or fleets in the vicinity. The first posting on a merchant ship must have come as a shock to many of the Commodores especially if they had reached the rank of Admiral in service. Rear Admiral Sir Kenelm Creighton returning to sea after a gap of more than four years recollected:

“… clambering up the vertical wire ladder dangling over the side. I chuckled inwardly, contrasting my present position with the pomp and circumstances that attended my arrival aboard my last command, the battleship Royal Sovereign, with her well-scrubbed gangway and mahogany rails, bosun’s pipes shrilling and the officer of the watch and quarterdeck staff rigidly at attention…. The Chief Officer yanked me inboard, my other hand collecting a lump of thick black grease on the way.”

The Commodore was not on his own. A key part of his role was communicating with the rest of the convoy so he had a team typically consisting of a Yeoman of Signals, Petty Officer Telegraphist, Leading Signalman and up to two Signalmen. In practice there was a shortage of trained signalmen especially at the start of the war.

For two years from the outbreak of war Kipper was Commodore of 12 trade convoys and a military convoy to the Middle East. The first convoys of 1939 were characterised by a total lack of experience on behalf of both the naval and merchant officers and a desperate shortage of escort ships. Many convoys put to sea with only one or two corvettes to protect them. There was no air cover for most of the voyage. The Masters were unable or unwilling to accept the discipline of sailing in close order or in observing and following signals from the Commodore. The demands of wartime meant that many old and unsuitable ships were pressed into service. All the ships in a convoy had to match the speed of the slowest vessel and this could be affected by the sea conditions, cargo loading, quality of coal carried as fuel and the state of the engines. All ships have their own optimal speed and some vessels become unmanageable if they have to travel too slowly. All these factors created headaches for the Commodore. The only saving grace was that Germany had a limited number of long range U-boats which were operating from ports in North Germany. Despite this 47 merchant ships were lost in the Atlantic in the first four months of the war. On top of all this Kipper had more bad news from home, his father John Lovell Robinson had died in December.

Things were to get much worse over the next three years. After the German victories of 1940 the U-boats were able to use bases in Norway and France and more long range boats were built. Between June and October 1940 they sank 274 merchant ships for the loss of 6 submarines and this success continued into 1941.The Battle of the Atlantic almost led to the defeat of Britain in 1940-42 as the enormous losses to merchant ships deprived the country of the supplies it needed.

In August 1940 Kipper was in command of convoy HX66. During the night of 29th/30th August the convoy was attacked by U-32 and three ships were sunk. The remainder were brought safely to port. Later that year the U-boats launched their first wolf-pack attacks. A line of U-boats were stationed across the route of the Atlantic convoys. When one of the boats spotted a convoy it would shadow it and call in the other U-boats. Finally they would launch a coordinated series of attacks on the convoy from different directions using their superior speed to avoid the escorting corvettes. In October 1940 convoy SC7 lost 20 out of 35 ships. Only 12.5% of Atlantic convoys actually suffered losses but every sailing was stressful for those involved, not least the Commodore.

Later in the war the development of technology to detect and attack submarines and better air coverage meant that the U-boats had less success and suffered more losses. Kipper served through the ‘happy time’ for the U-boats when every convoy was at risk and he could not afford to relax. In September 1941 at the age of 59 he was forced to retire from duty because of ill health and was sent home for treatment and rest. He was reunited with his daughter Sheila who had married was about to give birth. His sons Patrick and Tim were away on active service.

That year an early Christmas card was received from Tim who was serving on board HMS Neptune, part of the Mediterranean fleet under Kippers old classmate Admiral Cunningham. An aerogram with family news was sent in reply:

Dear old Tim

This should arrive about time to convey Xmas greetings. Hope you are OK & still enjoying life. I have now left hospital & am convalescing. Hope to be OK & in another job shortly. Patrick seems quite fit. Also Sheila and your nephew!! Haven’t seen him yet. Pro tem I am back on the retired list & will be glad to be off it for several reasons. Much love

Pop

The aerogram was returned with the message “Return to sender. Officer reported missing”. Tim’s ship HMS Neptune had been lost at sea.

On the evening of 18th December 1941, Force “K” the Cruiser Raiding squadron, led by HMS Neptune with Aurora and Penelope, escorted by destroyers, sailed from Malta to intercept and destroy a crucial Italian convoy, loaded with military equipment bound for Tripoli. In the early hours of 19th December Neptune struck a mine, disabling her rudders and propellers. She then drifted into other mines finally sinking before dawn. The Kandahar also struck a mine as she attempted to assist Neptune and the other ships were ordered to withdraw. 763 officers from the Neptune were lost along with 73 from the Kandahar. A memorial to the crews of the two ships was unveiled at the National Memorial Arboretum on the 9th July 2005.

Chapter 7. Kipper in Dundee

In June 1942 Kipper was fit enough for a new posting and he was appointed Naval Officer in Charge (NOIC) Dundee, a port at the mouth of the River Tay on the east coast of Scotland. Before the war Dundee was a small but important commercial port and a centre for the jute industry which rapidly switched to the production of sandbags at the start of the war. Like many towns and cities in Britain, Dundee was at first slow to react to the growing threat of war. In February 1938 Dundee Corporation passed a motion that the best protection against aerial bombardment would be international disarmament. As a result Dundee was poorly provided with air raid shelters or an effective system of civil defence. The first air raid on Dundee was in August 1940. On the 5 November 1940 the Secretary of Dundee Chamber of Commerce wrote to the Secretary of State for Air about the lack of anti aircraft defences for the city. The Air Ministry replied brusquely that no guns were available and that there were more important places to the war effort than Dundee.

It was true that Dundee was not a major industrial city but it was increasingly important as a naval port. Following the German occupation of Denmark, Holland and Norway, the North Sea and Norwegian Sea became critical battle zones and the city’s location was strategically important. It was a major submarine base for most of the war. The 2nd Submarine Flotilla with 9 submarines had been based at Dundee at the start of the war to blockade north German ports but in October it was suddenly withdrawn due to fears of German air raids. Then in April 1940 a unique submarine flotilla arrived in Dundee and remained here for the rest of the war.

The 9th Flotilla was an international force that included submarines and crews from the occupied nations of Poland, the Netherlands, France and Norway, as well as Britain. Dundee-based submarines operated in the seas to the north and west of Scotland as far as Iceland and east to the North Cape of Norway. They patrolled the enemy-held coastline of mainline Europe, attacking enemy merchant vessels and warships. They helped to protect the Arctic convoys carrying war supplies to Russia and landed agents on the coast of occupied Europe. Later in the war using intelligence provided by Bletchley Park they intercepted U-boats heading for the North Atlantic.

The decision to bring all these navies-in-exile together under one command and attempt to forge them into an effective fighting force was a risky one. A Dutch naval officer serving with the flotilla later summed up the difficulties in a light-hearted way:

‘All those nationalities, they were so different in their beings and needs. The Dutch wanted more potatoes, the French more red wine, the Poles needed love and the Norwegians for starters did not want anything from anybody. One mistake, one wrong decision, and the balance was lost. But this never happened.’

A naval historian, Mark C Jones, has written about the 9th Flotilla in an article Experiment at Dundee: The Royal Navy’s 9th Submarine Flotilla and Multinational naval cooperation during World War II. He points out that the Flotilla was a groundbreaking example of multinational cooperation and a model for post war cooperation in NATO. Jones believes that the success of the flotilla was largely due to the officers who were in command during the war. He highlights the role of the Captain (S9) who was in operational command of the flotilla and worked closely with the captains of the individual submarines. Kipper, as Naval Officer in Charge at Dundee would also have had an important role.

Kipper arrived in Dundee in on the 7th June 1942, taking over from Captain Hurt. His headquarters were on board HMS Cressy moored in Dundee harbour. HMS Creasy was a wooden frigate launched as HMS Unicorn in 1824 at the end of the Napoleonic wars. Although built in the style of ships of Nelson’s navy this was one of the first vessels to use iron fittings in its construction and marked the transition from timber built to iron built ships. The Royal Navy decided that they did not need to put the Unicorn into service so the hull was roofed over and she was put into reserve. Over the next few decades she was used as a store ship and in 1873 she was moved to Dundee. She initially served as the Drill ship for the Royal Navy Reserves and then in 1906 for the newly formed Royal Navy Volunteer Reserves. In WW1 Unicorn was used as the headquarters of the NOIC. It took on this role again in 1939.

In 1941 due to a clerical error the Admiralty mistakenly allocated the name HMS Unicorn to a new aircraft carrier. There could not be two ships with the same name so the Dundee ship had her name changed to HMS Cressy, though not before a number of ratings arrived in Dundee to join their new aircraft carrier only to find that much to their surprise they were boarding an old wooden frigate. Kipper would have been reminded of the old HMS Cressy torpedoed in 1914 with the live bait squadron which he had sailed with on HMS Amethyst.

As Naval Officer in Charge, Kipper had an important role. He was not responsible for the operational aspects of the 9th Submarine Flotilla – the Captain (S9) reported to the Flag Officer (Submarines) – but he would have worked closely with all the officers involved. In many ways his role was administrative. He was responsible for the efficient running of the dockyards and control of shipping in the area. He was also responsible for the defence of the dockyards. Secret orders issued in 1940 contained instructions that in the event of an enemy invasion the Naval officer in Charge was responsible for preparing demolition charges and sinking block ships to immobilize the port. He would have been responsible for the final defence of the harbour against the attackers.

However, his most important role was undoubtedly that of a diplomat, and in the multi-national setting of wartime Dundee this was to be very challenging. Kipper had to deal with a wide range of politicians, generals and heads of state from many countries.

Poland was represented by the submarines Wilk and Orzel (later joined by the British built Dzik) stationed at Dundee. In addition the Polish Army 1st Corps was responsible for defending the Angus coastline. The 1st Corps was made up of soldiers who had escaped from Poland in September 1939 and gone first to France and then to England where they were sent to guard the Scottish coast. The Poles were admired for their commitment to fighting the Nazis while individual servicemen in their smart uniforms and continental manners often made a deep impression on British women. However they were also a proud and independent people and some of their senior officers were both aristocratic and autocratic. This could make for difficult relationships with British officialdom. In one incident the captain of the Polish submarine Wilk based in Dundee was caught between his desire to stand up for the interests of his crew and the demands of his Polish superior officer. Unwilling to ask for help from his British commanding officer he committed suicide. The Polish Supreme Commander General Wladyslaw Sikorski visited Polish forces in an around Dundee on several occasions between 1939 and 1943 before he died in an air crash. Kipper undoubtedly welcomed him and his entourage to the dockyard.

Relationships with the Free French forces under General Charles de Gaulle could also be difficult. In May 1940 with the French army collapsing in the face of the Blitzkrieg many units sought refuge in Britain. French soldiers were evacuated from Dunkirk and vessels of the French Navy sailed to British ports with the French submarines Achilles and Rubis going to Dundee. The French forces intended to continue fighting as long as France remained in the war but in June the French government surrendered. The majority of the French armed forces believed that for them the war was over and that they should return to a defeated but still independent Vichy France. General de Gaulle vowed to continue the fight against the Germans and on the 18th June 1940 he issued his call to continue the war. Winston Churchill meanwhile was worried that the ships of the Vichy French navy might eventually fall into the hands of the Germans and on the 3rd July the French fleet in Algeria was given an ultimatum to either join the British or scuttle their ships. When they refused British warships opened fire sinking a battleship and killing over 1,000 French sailors. The attack caused great bitterness especially within the French navy and helped increase support for the Vichy government and anti-British sentiment. Of the 20,000 French sailors in Britain at the time only 400 rallied to the Free French cause.

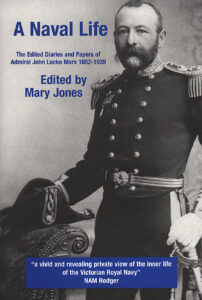

Eric Robinson with General de Gaulle in the wardroom at HMS Ambrose, the shore establishment of the 9th Submarine Flotilla, Dundee. Robinson is in the uniform of Captain, his rank as Naval Officer in Charge, Dundee 1942-44. It came from www.sectionrubis.fr – via the Unicorn Preservation Society.

Eric Robinson with General de Gaulle in the wardroom at HMS Ambrose, the shore establishment of the 9th Submarine Flotilla, Dundee. Robinson is in the uniform of Captain, his rank as Naval Officer in Charge, Dundee 1942-44. It came from www.sectionrubis.fr – via the Unicorn Preservation Society.

The British recognised that this attack on the Vichy fleet would cause problems with the French ships in British ports and so Operation Catapult was launched on the same day to board these ships as they lay at harbour. In Portsmouth the crew of the submarine Surcouf resisted and two Royal Navy officers and a French sailor were killed. The operation was handled better in Dundee. The Flag Officer (Submarines) wrote to the Captain of the Rubis expressing his complete confidence in the loyalty of him and his crew and expressing regret for having to restrict them to barracks for a short time. In return the French submariners promised to follow the lead of their Captain and stay in Britain. Rubis went on to play an active part in the war against Germany.

De Gaulle continued to build up the Free French forces in Britain but his dealings with the British establishment was marked by suspicion and hostility on both sides. He visited Dundee on several occasions, often with Admiral Muselier, commander of the Free French navy. These meetings with the NOIC had the potential for being extremely difficult but in January 1943 he met Kipper and afterwards wrote thanking him for the help he was giving. After the war Kipper was presented with the Legion d’Honneur and the Croix de Guerre with palm “for the most valuable services rendered in the common cause and for your cooperation with the French Navy during the war”. Clearly the French General had been impressed by the British Admiral.

A few months later De Gaulle boarded a plane at Hendon airfield for another inspection of the Free French navy in Scotland. The plane crashed on takeoff but fortunately De Gaulle survived. The cause of the crash was sabotage and ‘enemy agents’ were blamed but De Gaulle himself believed that the British had tried to get rid of him.

The Norwegians were the third occupied country to have submarines in the 9th flotilla. In April 1940 Germany invaded Norway and King Haakon VII fled to Britain to set up a government in exile. His Norwegian’s Majesty Submarines Uredd, Ula and Utsira joined the 9th flotilla. In addition, the minesweepers assigned to Dundee for much of the war were from the Royal Norwegian Navy. Eventually, a Norwegian officer was put in charge of all minesweeping efforts at Dundee and he would have reported to Kipper. The Norwegian naval air service also had a squadron in north-eastern Scotland. King Haakon visited Dundee in July 1944 and again Kipper must have made a good impression for after the war he was awarded the King Haakon Freedom medal.

The final contingent in the flotilla was from the Netherlands which had been invaded on the 10th May 1940 and overrun in five days. Five Dutch submarines and the mother ship Colombia were based at Dundee. One of the first distinguished visitors that Kipper had to deal with was Prince Bernhard, son-in-law of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, who piloted his own aircraft into Tealing Airport on the 25th June 1942. Kipper would have had to entertain him and assure him of the valuable contribution being made by the Dutch submarines – two of which – O13 and O22 – had been lost at sea. But Kipper was facing his own personal tragedy. That same day his eldest son Patrick was shot down in a bombing raid over Germany. Patrick had joined the Royal Navy before the war but after two years he left to take up a civilian job. On the outbreak of war he volunteered to join the RAF as a navigator and was posted to 102 squadron at Dalton in Yorkshire, operating Halifax bombers. His body was recovered at sea by the Germans and was interred at the Wiltmund military cemetery near Wilhelmshaven. After the war his body was moved to the British Military Cemetery at Oldenburg.

Now aged 60 Kipper had lost both his sons. His brother Ernest had been killed in 1914. His mother had died in 1938 and his father in 1939. Only his sister Mary, his daughter Sheila and grandson Sean survived.

Although Kipper would not have been aware of it at the time, the tide of war was beginning to change. In December 1941 the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour had brought the United States into the war. In October 1942 General Montgomery defeated Rommel at the battle of El Alamein and in November the Red Army surrounded the Germans at Stalingrad. In Dundee the coastal defences against invasion were stood down in May 1942 and the last major air raid took place in August. Operations by the 9th flotilla continued to take the war to German forces in the North Sea. In February 1943 the Norwegian submarine Uredd left Dundee to patrol off the Norwegian coast. As well as its normal crew Uredd was carrying a party of British and Norwegian agents who were to be landed on a sabotage mission. The submarine hit a mine off the Norwegian coast and sank with the loss of 34 crew and 6 agents. Even today these special missions are shrouded in secrecy. Kipper would not have been involved in the details of the operation but as Naval Officer in Charge he would have been aware of the nature of this mission. In June there was a more successful operation. Acting on decoded Ultra intercepts HMS/m Truculent intercepted and sank the U-308 on its way to the Atlantic to attack Allied convoys. In May the following year HMS/m Satyr sank the U-987. As an ex-Commodore of convoys Kipper would have appreciated these blows against an old foe.

Most of Kipper’s time would have been spent on the routine of running the port. He would have had to attend parades through the streets of Dundee designed to raise morale. Important visitors such as King Haakon of Norway and General de Gaulle would have to be entertained. These visitors would not have failed to notice the purple ribbon of the Victoria Cross on his uniform and would have known that although he held the acting rank of Captain he was a Rear-Admiral. No doubt he regaled his guests with stories of his past exploits. One VIP who Kipper did not have to worry about was the Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Churchill had been the MP for Dundee in the 1920s but had lost his seat and departed vowing never to set foot in the city again. When in October 1943 the Corporation debated awarding him the freedom of the city the motion was approved by only one vote. Churchill turned down the honour.

In the summer of 1944 sailors from the Soviet Union arrived in Dundee for training to operate four British built submarines. Kipper would have been aware of the potential of trouble between the Russian and the Polish sailors. For many Poles, Russia was still the enemy. When Russia invaded Poland in 1939 Polish soldiers and civilians were rounded up and put into labour camps. A large number of Polish officers, government officials and intellectuals disappeared and in 1941 the invading Germany army discovered mass graves of Poles massacred by the Russians at Katyn. The Polish government in exile broke off diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union over this. The Polish forces were desperate to liberate Poland but by 1944 it became clear that the Red Army would get there first. In August the Red Army was on the outskirts of Warsaw and the Polish government instructed the underground Polish Home Army to launch an armed uprising to liberate the city before the Russians arrived. The Russians then halted their advance allowing the German forces to put down the rising. Trouble between the two groups of sailors in Dundee was avoided but the story had a tragic end when one of the Soviet submarines (B1 ex-HMS/m Sunfish) was sunk by the RAF in error as it sailed back to Russia.

With increasing poor health and age Kipper prepared to hand over command at Dundee to his deputy. One of his last official duties was to authorise the sailing of HMS/m Venturer on another mission to intercept U-boats. The day after Kipper stood down Venturer torpedoed the U-771.

Kipper had undoubtedly contributed to the success of the 9th flotilla through his administrative and diplomatic skills. It was now clear that victory against Nazi Germany was within reach and for the second time in his career Kipper could retire.

Chapter 8. Kipper stands down

After the war Kipper retired to the village of Langrish, near Petersfield in Hampshire. He lived at “The Old Toll House” later known as The White House. His public services continued as a church warden, member of the parochial church council and member of Petersfield Rural Council. In 1956 he featured in the local paper making a plea on behalf of two elderly spinsters who were being threatened with eviction from the village Post Office which was being closed down.

Kipper died at Haslar Naval Hospital on 20th August 1965 and was buried in St John’s churchyard, Langrish. On the 20th August 1998 a ceremony was held at St John’s church to dedicate a memorial grave stone. The ceremony was attended by two of Kipper’s three grandchildren – the children of his only surviving child Sheila who had married John Millen in 1939 – Sean, Sara and Nicholas (Peter).

Also at this ceremony was a representative of the new HMS Vengeance, a Vanguard class nuclear-powered Trident ballistic missile submarine then under construction at Barrow-in-Furness. The new Vengeance, the eighth of its name, was interested in the link with Kipper who had won his VC while serving on the sixth HMS Vengeance. Kipper’s granddaughter Sara Clayton was invited to the rolling out and the commissioning of the new submarine.

Eric Gascoigne Robinson VC was now at rest. He had had an eventful life, loyally serving his country whether it was for imperial expansion in China or defending his homeland against fascist aggression. He had shown outstanding bravery under fire, was an inspiring leader of men and a skilful diplomat. He had survived two World Wars which had claimed his brother and two sons. He was by all accounts a modest man who lived through extraordinary times and performed extraordinary deeds. He deserves to be remembered as both a typical example of his generation and a unique individual.

© Carl Clayton January 2012. Revised June 2022

If you have any comments please email: cclayton[at]hotmail.co.uk

To read Part 1 click here

Bibliography

| Anon | The Royal Navy on the Caspian, 1918-1919. Naval Review, 7/8 1919-20. pp87-99 and 218-240 |

| Anon | Baku during the British Naval campaign on the Caspian in 1919. Naval Review, 7/8 1919-20. pp241-269 |

| Anon | A narrative from the Caspian Sea. Reconnaissance of Fort Alexandrovsk, May 21st 1919. Naval Review 7/8 1919-20 pp520-526. |

| Anon | Deeds that thrill the Empire: true stories of the most glorious acts of heroism of the Empire’s soldiers and sailors during the Great War. Part XI. Hutchinson, 1917. |

| Anon | Obituary. The Times. 23 August 1965 |

| Burn, Alan | The fighting commodores: the convoy commanders in the Second World War. Leo Cooper, 1999 |

| Carruthers, Bob | Wolf pack: the U-boats at war. E-books edition. Coda Books, 2011 |

| Chang, Jung | Empress Dowager Cixi. Vintage 2014 |

| Fleming, Peter | The Siege at Peking, OUP, 1984 |

| Jeffrey, Andrew | This dangerous menace: Dundee and the River Tay at war, 1939 to 1945. Mainstream, 1991. |

| Jones, Mark C. | Experiment at Dundee: the Royal Navy’s 9th submarine flotilla and multinational naval cooperation during World War II. The Journal of Military History 72 (4) p1179-1212. 2008 |

| McGinty, Michael | HMS Vengeance – more than just a name. Commissioning Book – 27th November 1999. WTE (Scotland) Ltd, 1999 |

| Mills, Steve | The WWI Remote Control Boats of the Royal Navy: the secret DCB section and their amazing drones. Unpublished paper. (see Wikipedia article British unmanned aerial vehicles of World War I – Wikipedia) |

| Nykel, Piotr | Personal communication quoting the official Turkish history of the Dardanelles campaign. See http://navyingallipoli.com |

| Smith, Ken | Turbinia: the story of Charles Parsons and his Ocean Greyhound. Tyne Bridge Publishing, 2009. |

| Snelling, Stephen | VCs of the First World War. Gallipoli. Allan Sutton, 1995. |

| Winton, John | Cunningham: The Greatest Admiral since Nelson. John Murray, 1998 |

| Other sources of background information include Wikipedia and other on-line resources. | |

| Archives | Family archives held by the descendants of Eric Robinson |

I assume that you are unaware that Robinson commanded the secret Distance Control Boat Section at Calshot set-up on 1/9/1917. This unit used Distance Control Boats (converted Coastal Motor Boat designs) and other vessels to develop remote control equipment. This is probably omitted from his diaries BECAUSE IT WAS SECRET. This was the period when he was first introduced to the CMBs