Persona Naval Press is pleased to welcome the second two articles from Marjorie Rear, MA (Oxon) who has edited the letters of her husband’s ancestor, Captain Charles Barker RN, 1811-1860.

A number of letters written home by Captain Charles Barker, RN (1811-1860) are preserved in Sheffield Archives with other family papers.1 There are frustratingly long gaps in the sequence as they were obviously handed around the extended family and not all returned to the care of his mother, Sarah. They do, of course, contain a great deal of personal material, but there is, however, enough to make interesting reading for students of naval – and imperial – history during this period when the Royal Navy has been described as “in transition”.2

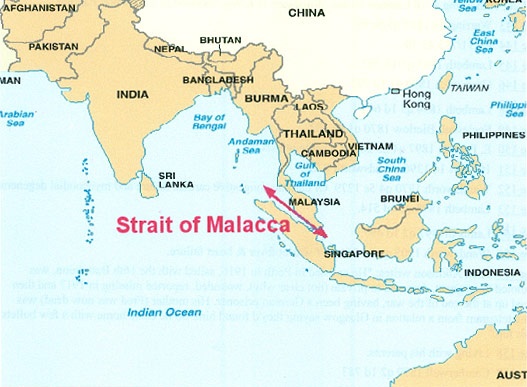

At last in command of his own ship, the ten years between 1849 and 1856 show Charles Barker carrying out naval duties, first, in the Straits of Malacca and, then, off the west coast of South America, in what one might call the “workaday” peacekeeping role of the Royal Navy. Perhaps he and his officers might have wished to take the opportunities offered of more glorious action in China or the Crimea, but Britain’s increasing trade and colonial aspirations depended upon the maintenance of the freedom and safety of the seas by a naval presence wherever this might be threatened.

In September 1849 Charles Barker, still with the rank of commander, was appointed as captain of HMS Serpent, a 16-gun brig-sloop destined for the East Indies and China station. Whatever he had learned about steamships serving in Firebrand had to be set aside as his new command was a sailing ship over twenty years old. When he left Plymouth in November he was quietly pleased with her and able to write home that she had been improved by some alterations made at Plymouth so that she

. . .sails well. She has made 435 miles in the last two days and is now going ten knots as quietly as possible. Finding our decks rather leaky and having a little repair to do to part of the rigging which cannot be got at while at sea, I have quite determined on going to Madeira if possible. I continue to like the officers and have a very good crew – of course some rather slack hands who want rubbing up and will get it. I wish you could have seen them knocking the guns about this evening when I took everyone by surprise by going to quarters for exercise.

By the following March he had reached Singapore via the respective Straits of Sunday, of Borneo and of Durian, expecting to be half way to Hong Kong by April 9. There was no firm news of his ultimate destination; though his guess was Serpent would be sent to the Northern ports of China “to look out for pirates of which there are still several in spite of the numbers lately destroyed.”3 In Singapore he found Commodore James Hanway Plumridge who had been Commander-in-Chief of the station since the death of Admiral Francis Augustus Collier in October. Commodore Plumridge was found to be “very civil”, though Barker could not resist remarking that (aged 63) “he had married a young woman as far as I can judge remarkable only for folly and bad temper.” To his mind there was, unfortunately, to be an imminent change:

Admiral [Charles John] Austen is expected by the next mail. I fear he is too old for his post even should I think him in other respects very well fitted for it as he was considered pretty much of an old woman when he commanded the “Bellerophon” in the Mediterranean.4

Barker’s expectation of orders for North China were confounded. At Hong Kong while he was awaiting further orders, Captain Edward Norwich Troubridge, Captain of Amazon, died on 28th September 1851 and the following day5 Charles Barker was at last promoted to the rank of Captain and took his place, only detained on the China coast by the necessity of awaiting Amazon’s relief, Contest, with her captain, Commander John W.S. Spencer. Instead of chasing pirates in the China Seas, he found himself instead faced with the perennial problem of piracy in the seas around Singapore, The Phillipines and Borneo. Writing home from Hong Kong in November his attitude is optimistic:

We are now quite ready for sea and sail on Wednesday the 20th for Manilla and thence to Singapore and the Straits of Malacca, that place and Penang being the principal ports. There I am to remain as Senior Officer and believe it to be a healthy and agreeable station. I never expect to return to China, and although I should like to have visited the Northern ports, do not regret getting away from what I consider as the most abominable and unhealthy station in the world, I certainly have never suffered so much from climate on any other, though I am thankful to say I am now quite well. . . I shall find the “Lily” with Captain [Robert Tench] Bedford at Singapore and she is to be under my orders for some time.

Charles Barker had, of course, visited this area earlier on his way out to China in Serpent, incidentally becoming a great friend of John Harvey, later director of the Borneo Company6, and would have been familiar with the problems of piracy and its effects on trade in the area. So far as the Straits of Malacca specifically were concerned the Malay pirates operated there in large fleets of well armed prahus7, preying on sailing ships helpless in the frequent calms between October and January.8

There are no letters home covering this period.9 There are preserved, however, some copies of official correspondence between William Butterworth, the Governor of Prince of Wales’s Island, Singapore, & Malacca, and Lord Palmerston, the Foreign Secretary. Quite why these should have been kept by Barker when the events being discussed took place a considerable distance from the Malacca Straits is unclear; presumably they were sent as a matter of courtesy to all squadrons in the South China Sea.

What this collection of letters appears to show is that, so far as Britain was concerned, suppression of piracy was not the sole reason for a British presence in the area. Equally important was increasing the sphere of British interests in the area against that of the Spanish, reaching out from their base in Manila. A treaty, with the usual clauses of “favoured nation status” and mutual action against slavers and pirates, had been signed with the Sultan of Sulu on May 29th, 1849 and was due to be ratified by Spenser St. John, Acting Commissioner in Borneo, in May 1851. However, circumstances had changed with an attack by the Spanish on Sulu, under the direction of the Captain General of Manila, Antonio Maria Blanco.10 James Brooke (the “White Rajah” of Sarawak) was, for his own trading reasons, anxious that ratification should go ahead, hoping for the establishment of a British colonial presence in the area:

In case the Spaniards are repulsed, the ratification of the Treaty should be exchanged with as little delay as possible and, in case the Spaniards prove victorious, it would still be desirable that a vessel should proceed in due season to Sulu to prevent any claim being set up to the Eastern coasts of Borneo, as well as to enquire about the Pirate hordes of Turka, Tanee, Taree, and other places.

However the British must have decided that ratification of the treaty, with its consequent obligations to the Sultan of Sulu which might result in difficulties with Spain, was too risky an undertaking. The Sultanate of Sulu managed to keep its independence without British assistance and the British navy abandoned the possibility of using its “ports, rivers and creeks . . .to provide themselves at a fair and moderate price with such supplies, stores and provisions as they may from time to time stand in need of.”11 In the absence of any demonstration of the Sultan’s good faith and the continuation of piracy in the area, this was rightly thought no great loss.12

Another of those regrettable and inexplicable gaps in the correspondence follows. The next extant letter is from Retribution in harbour off Malta in February 1857. Retribution was a 1st class 10-gun frigate, powered by paddle steam engine and had previously been employed in the Crimea. She had been paid off on 23 August 1856, but re-commissioned the following day for service in the Mediterranean. Charles Barker was appointed as her captain on the 30th August and obviously enjoyed the opportunities offered by Malta for meeting old naval friends. Only the downside of being on board a steamship dampened his pleasure:

We have to tow home Her Majesty’s Gun Boat “Grinder” and a great bore it will be, but it cannot be helped. She will not detain us much unless she breaks adrift or it should come on to blow so hard that she is obliged to “lie to.”

By the following month, however, he had orders for Rio de Janeiro. Sailing to Teneriffe on the first leg of the voyage, Amazon had to contend with such bad seas that twelve panes of glass were smashed, flooding the captain’s cabin to a depth of six inches, resulting in its having to be completely boarded up. From Teneriffe, however, the weather improved:

We steamed into the breeze for about half an hour and have been under sail only ever since, which has been delightful, and we have had a fine time for painting which is now nearly finished. You may think what a job it is when I tell you we had about 3,300 square feet to paint, all with two coats and two-thirds with three, besides our gun carriages . . . perhaps about 10,000 feet in all.

Nearer the equator, on Good Friday, weather worsened again requiring Barker to abandon sail power, but he admitted that using steam did have its compensations:

No wind and a very heavy atmosphere with the thermometer 86o in the shade. Tremendous rain in the night. We hope to get the SE trade today or tomorrow and shall be delighted to put the fires out. . . We are reaping the benefit of the condensing pipe I had fitted, having condensed about 24 tons since we lighted fires. We make at the rate of 15 tons a day which enables us to have as much of that luxury as we want and use two and a half tons daily. What we should have done without it, I can hardly imagine.

No doubt the lovely new paintwork suffered from the smoke and cinders even if there was plenty of water to wash it – and the men – down. There were other problems consequent on the use of steam power. It had been some years since chief engineers had been designated as commissioned officers to allow them to communicate with the captain directly rather than through an officer, but those in charge of the engines still seem not to have been fully integrated into the crew and this separation may not have helped towards an acceptance of the advantages of steam power.

We crossed the line yesterday and had all the usual ceremonies and everything went off very well and good-humouredly, except that the engineers foolishly held out against being shaved, and as I did not choose to have a row, they escaped, but have incurred the dislike of the whole ship’s company which manifested itself against them last night and obliged me to take measures to check in the bud.

By May 5th 1857 Retribution arrived at Rio, to find the Pacific squadron much reduced by the transfer of ships to the China war. His next destination was to be Valparaiso, but damage to the rudder required the ship to call at Stanley in the Falkland Islands.

I look upon this settlement as a most valuable place of refuge for vessels disabled in these stormy regions, and it is a great pity there are not more means available for their repair, for although stores of many kinds can be procured, there are no artificers. Were they to send out a large number of convicts to construct a patent slip it would be much better than giving them tickets of leave at home. . . Cattle thrive here well and we get very fair meat at two pence a pound, very good at four and a half pence a pound. Vegetables also grow very fairly and we get good potatoes at three pence a pound, turnips at 2d, also cabbages and leeks. They have also very good mutton at nine pence a pound. Flour is dear but grocery items quite as reasonable as can be expected. The wild upland geese and rabbits are cheap and good. The Governor is Captain [Thomas Edward Laws] Moore who commanded “Plover” in the Baring Straits. He is a very pleasant companion. The society is very small, but people seem on good terms with each other, which is not generally the case in these small communities, and they are very civil and hospitable.

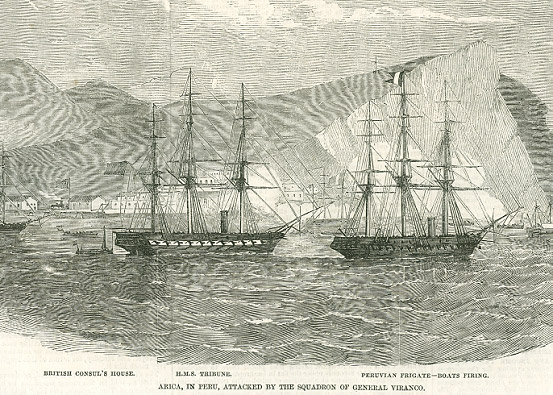

The reason for Retribution’s presence off the long coast of Peru was that a revolt against the President had led to most of the Peruvian navy being in the hands of the revolutionaries. Earlier two of these gunboats had stopped the British mail-steamer and robbed it of money and supplies.13 Fighting between Government forces and the rebels led to HMS Tribune under Captain Harry Edgell appearing at Arica and offering asylum to the threatened foreigners.

Engraving from the Illustrated London News, January 24 1857

Engraving from the Illustrated London News, January 24 1857

Retribution arrived in the area via the Straits of Magellan after an interesting voyage described in some detail. From Santiago on 12th July 1857 Barker noted that he would be sailing in a few days to meet the Admiral [Henry William Bruce in Monarch]14 at Callao, calling at Arica and Islay on the way, but “a lady told me today that we were going to the Chincha Islands to look after the guano.” Gossip seems to have travelled faster than orders. Barker did in fact find himself patrolling, in the company of Vixen,15 the Peruvian coast between Arica and Valparaiso, “chiefly at the Chincha Islands”. These three islands had vast valuable deposits of guano, of vital importance as fertiliser and therefore of considerable monetary value to whoever controlled access.

This was not to be an easy assignment. The Consul-General in Peru, Stephen H. Sulivan, had been mortally wounded in Lima by an assassin “possibly on account of a Guano treaty which Mr. S. had concluded and which cuts off that source of revenue from the rebels”, and the presence of a rebel gunship. Barker regretted that he had no opportunity to speak to the Admiral

. . .as there are many points connected with the possible state of affairs here and many proceedings connected therewith on which I wished to have consulted him, as a captain of a man of war here may be placed in a situation of great responsibility. . . The non-ratification of the Guano Convention has caused great dismay here as it is feared the rebel frigate “Apurimac” will again take possession of the Chincha Islands and sell guano on their own account and thereby raise funds to carry on the war. I cannot now interfere beyond seeing that our vessels are not molested or delayed.

Difficulties continued. In October the town of Islay appears to have been blockaded by the rebel frigate, leaving Barker with a moral dilemma:

The people are suffering much from want of provisions and water, particularly the latter. I supply the foreigners with the latter, but feel I have no right to do so to the natives, as by want of water they [the rebels] hope to cause the fall of the place. It is cruel work and one of the miseries attendant upon war.

Fortunately he was able to report that

The Admiral writes most handsomely about my proceedings at Islay. He begins, “you have had no easy occupation, but you have the satisfaction to know, that in your case ‘the right man has been in the right place’ and ends “I only regret not having been at Islay myself in as far as it would have relieved you of responsibility. For the rest I should have acted as you have done.”

Difficulties requiring both naval force and political diplomacy continued, however:

The anger of the Captain and officers of “Apurimac” at my watching her does not decrease and received a little fillip the other day by my taking out of her an Englishman serving against his will and with no written agreement, and insisting on his being paid his wages . . Our merchants at Iquique are suffering such heavy losses from the stoppage of trade through the measures adopted by the Government party that I have come here [Arica] to see if no arrangements can be entered into to allow its resumption, and go to Tacna tomorrow to see the Prefect.

“Apurimac” had gone to Islay to prevent the mail steamer landing supplies at that place . . . bringing me more trouble. She had interfered with the packet improperly and had pressed out of a vessel one French and two Sardinian subjects. The first I demanded and requested the latter & they are on board waiting to return by the next steamer. I saw General Rivas [captain of the rebel frigate] and gave him such a talking to about interference with the Packet that I hope there may be no more of it. Should there be, I have told him I shall, by force, put out of her every Peruvian authority of whatever rank.

Retribution also had to make an expedition to Cobija in Bolivia “to make enquiries respecting the attack on an English mining establishment at Tocopilla”. They found the miners who had suffered were “all from one parish in Cornwall” and were delighted to have the ship’s chaplain go ashore to baptise two of their children.

It was a relief to Barker to be able to report in March 1858 that the Peruvian revolution was over and the rebel squadron, which had been such a pain in his side, was giving itself up to the Government forces. The British government immediately seized on this less volatile state of affairs to take the opportunity of ordering Retribution – and Magicienne – to China post haste: “I received my orders direct from the Admiralty so they are evidently desirous we should lose no time, which would have been the case had they gone through the Admiral”. In spite of a successful attack on Canton, the Chinese authorities were still proving obdurate in abiding by their obligations under the Treaty of Nanking and naval reinforcements were badly needed.

The final phase of Charles Barker’s career was to be on the China Station.

References

- The letters and papers of Charles Barker, Sheffield Archives, Bar D 801/69-110. The quotations in this article come from 801/79-101 & 801/45-52, 801/59 and 801/82.

- Michael Lewis, The Navy in Transition: a Social History 1814-1864, Hodder & Stoughton, 1965.

- See W.L. Clowes, The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Vol VI, pp. 358-359.

- Austen commanded Bellerephon from 1838-1841. (This was, of course the ship of that name launched, as Waterloo, in 1818, not the renowned “Billy Ruffian” of the Napoleonic Wars). [www.pdavis.nl/SeaOfficers]. Barker must have gathered this opinion while he was a lieutenant in Monarch, also in the Mediterranean.

- Troubridge’s death seems to be universally given in biographies such as Paul Benyon’s Index to Extracts from Various Navy Lists 1844-1879 [www.pbenyon.plus.com] as October 1850, while still Captain of Amazon, but the Ship’s log [PRO ref. ADM53 3847] is presumably correct.

- At this time John Harvey was Manager of MacEwan & Co. in Singapore, the agents of James Brooke, ” The White Rajah”. His letter to Charles Barker, written in September 1850, was sent home to Bakewell presumably because it contained mention of a happy visit Harvey made to the Barkers in Bakewell. Harvey later became a director of the Borneo Co. Henry Longhurst, The Borneo Story, Newman Neame, London, 1956.

- These local sailing boats – originally for fishing – could be adapted for speed with thirty-six oars, arranged in tiers, and were armed with small cannon, swivel guns, muskets and spears.

- See C.M. Turnbull, The Straits Settlements 1826-67, University of London Historical Studies XXXII, pp. 243-4.

- We do know that on April 28 1851 Amazon was at Campong Glaur, Palawan island. Ship’s Log [PRO ref. ADM53 3847] There Commander Crawford Pasco, who was on the Royalist survey ship met his “old friend” Charles Barker and recounted in his reminiscences that Barker “who had not seen me since he was a boy more than twenty years before . . . was so shocked at my appearance that he said at once, ‘you must be invalided; I will send my surgeon to consult with you at once.'” Crawford Pasco, A Roving Commission, George Robertson & Co., Melbourne.

- Provoked according to the Spanish, but quite unprovoked according to a letter from the Sultan in an appeal to James Brooke.

- Article 4 of the Treaty.

- For example, in 1872 the survey vessel, Nassau, landed a boat on Sulu island to take bearings and was attacked by a large number of pirates. One officer was wounded. W.L.Clowes, op.cit., Vol. VII, p. 232.

- See Clowes, op.cit., Vol. VII, pp. 137-8.

- His appointed successor, Admiral Baynes in Ganges, arrived at Valparaiso only in January 1858.

- Paddle sloop; Commander George Mecham.

Marjorie Rear MA (Oxon) May 2008